Jam knows there are no monsters left in Lucille. She knows this because everyone knows this, because all the terrible people who liked hurting everyone else were killed in the revolution that took them out of power in the government and in jobs and in homes, and freed everyone from their selfishness and cruelty.

That hasn’t kept her from wondering what monsters really looked like, though, if they had horns and claws or looked no different from her parents or her best friend, Redemption. People don’t like to talk about the monsters anymore, don’t want to dwell on a time everyone knows is over. But Jam imagines that they looked just like any other person. That that was why they stayed in power for so long.

When a creature made of horns and claws climbs out of one of Jam’s mother’s paintings, it certainly looks like a monster. But instead, Pet—for that is the creature’s name—is hunting one, a monster that has slipped through Lucille’s cracks and lives among them. Among them, and in Redemption’s house, no less.

Jam doesn’t want to believe it. After all, who wants to believe in monsters? It’s far prettier to believe that all the monsters are gone, just like she’s always been taught. It’s far easier to look away from the wrongs that could be happening, just underneath her nose.

But Pet won’t let her look away anymore. And the only thing more difficult than realizing that there still are monsters is daring to look them in the eye.

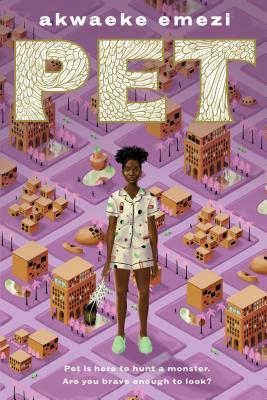

Pet is truly incredible. Powerful, succinct, and layered despite its relatively low page count, I’ve wanted to read this book for years, and it didn’t disappoint. There are few authors who can pull off such a deep, philosophical story without ever feeling preachy or contrived, but Emezi does it effortlessly, weaving a story as profound as it is profoundly unique. They take familiar tropes—dystopia/utopia, monsters and angels—and turns them into something as unfamiliar and jarringly powerful as Pet itself. The humanity of the characters—even Pet, who is anything but human—grants Pet even more depth, and the conflicts and worldviews they each present help weave Lucille into a world that is devastatingly believable, one where everyone would rather believe in the world’s good than see the monsters lurking among them. At once a searing critique of forgetting and complacency and a challenge to the hideous monsters we’ve all been taught to believe in, Pet is a perfect read for book groups or anyone who wants to see their own beliefs challenged, and dare to, as Pet tells Jam, truly see the world for what it is. I highly recommend Pet to readers ages thirteen and up, particularly those who enjoy books that defy easy boxes or have a queernormative society.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed